History

Hausa and Berta Conflict in Sudan: How did the Hausas get to Sudan?

Ifeoluwa Siddiq Oyelami

Since July, there have been continuous clashes in the south-eastern Sudanese state of the Blue Nile between the Hausa and Berta ethnic groups. So far, these clashes that have led to the death of scores of people are linked to issues bordering on land ownership and leadership inclusiveness. Even though some observers have said that it only escalated because of the Sudan military government’s policies that have put the various ethnicities against each other after the government of Omar Bashir was toppled. While we have been trying to follow the events in Sudan, we should note that this article is not to discuss the conflict but to answer one of the questions about how the West African Hausas got Sudan. This question was left blank on an Al Jazeera English July 19 publication, which states, “It is not clear how the Hausa got to Sudan.”

The Hausa people are a sizable and influential group across most of West Africa, but mainly in Nigeria’s north-western region. Although there are many legends about how and why they got there, the fact remains that they have been in the area for generations, established their own kingdoms there, and had generally converted to Islam by the 15th century. In contrast to their Fulani neighbours, whose pasture has caused them to disperse over West Africa for centuries, the Hausas are predominantly settlers. However, one wonders how some of them ended up in Sudan as neighbours of the East African Bertis, with whom they are in conflict.

As we will discuss, the Hausas or the Hausa language-speaking people in Sudan or their parents or ancestors might have found their way to Sudan on three occasions with socio-religious backgrounds.

Hajj

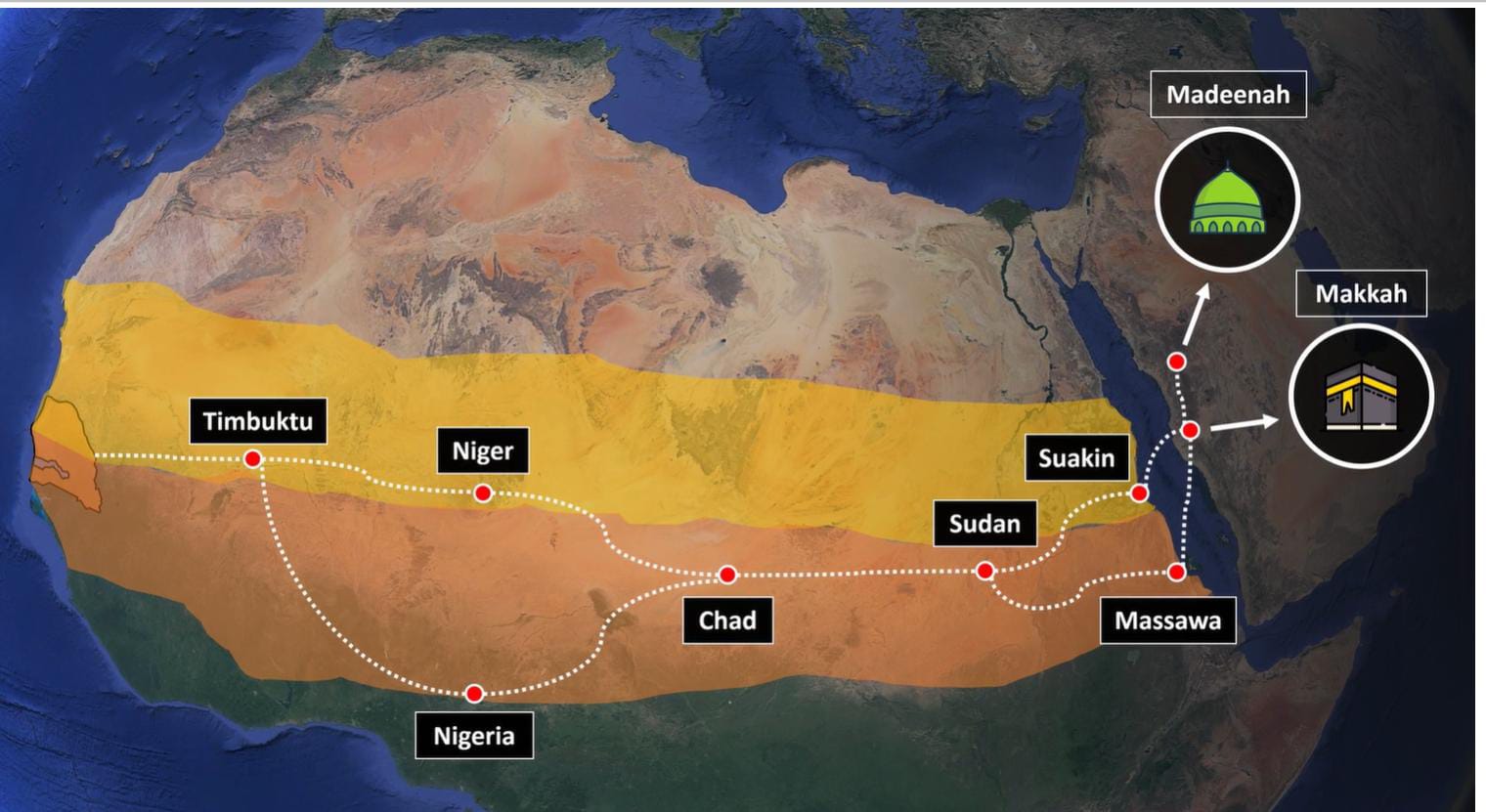

Although we cannot put a date for when the people from Hausaland started to venture on the Hajj journey through Sudan, it was sure that this route became busy in at mid-19th century when the European invasion took over other routes by West African Muslims. This route change made many pilgrims from Timbuktu and Senegal pass through Hausaland to Sudan. This, coupled with the increased Islamic orientation in the 19th century, might have increasingly encouraged Hausa to go on pilgrimage. However, due to how they embarked on the hajj journey, many Hausa-speaking people comfortably settled in Sudan on the path to the house of Allah. For them, Hajj was more than just a trip to Makkah and back; it was a pilgrimage that may ultimately take them away from their native lands forever. They may occasionally stop by on their way to study or work, as the Maliki madhab allows. Sometimes, marriage and subsequent settling down will occur from such a stay. Because of this, many Hausas adopted Sudan as their home before the middle of the 20th century.

A map showing Hajj Routes in the 19th CenturyWest Africa' (Source: Ilm Institute)

The Mahdism Movement

One of the effects of all-around colonial campaigns in Muslim Africa is the emergence of an apocalyptic atmosphere. Many anti-colonial movement leaders went under the delusion that they were the Mahdi. One prominent one among them was Muhammad Ahmad from Sudan, who created a movement called al-Ansar. His group fought the Khedivate ruler of Sudan and subsequently the British colonial power, hoping to establish pristine Islam.

In response to the call of Muhammad Ahmad, many people across the region joined his rank, including a vast number of the people of Hausaland. The emigration rate was so high that the then Amir of Kano (in today’s Nigeria) Muhammad Bello had to write to Maryam Uwar Deji, the daughter of Uthman ibn Fodio, asking her to advise on the mass migration. The latter sent a comprehensive letter to him stating that the migrating people were acting in ignorance.

The Fall of Sokoto

At the turn of the 20th century, the colonial powers had taken over most of Africa, and one of the last standing places was the Sokoto caliphate which was created as a unifying Islamic state in what is known as Northern Nigeria and its environs today. In 1900, the Sultan of Sokoto, Abdurrahman, understood the imperialist intents of the “initially friendly” British, so he suspended his relationship with them. In response to this move, British high commissioner Fredrick Lugard declared war against Sokoto to ascertain the sovereignty of the British over the whole territory of today’s Nigeria.

Although Sokoto initially put out a strong resistance, by 1903, it fell to the British advancing from the south and the French forces advancing from the North and East. The Sultan, Attahiru I, was killed by the British. Thousands of residents who did not favour living under the invaders’ government moved one with Muhammad Bello Mai Warno, the son of the late sultan, to join the Mahdi movement, which was still putting out a fight against the British in Sudan.

Conclusion

These three events explain why we have Hausas in Sudan today. These three events show that the Hausa’s migration was not a demographic usurpation but a consequence of religious pursuits. Moreover, it all symbolises how the borders within the larger Bilad al-Sudan were not an obstruction to brotherhood. Furthermore, it demonstrates the hospitality of the people of Sudan as the custodian of the path to the house of Allah. We pray and hope that the Hausas and Bertis of modern-day Sudan, inspired by the religious brotherhood of their ancestors, will examine their crisis and come up with a durable solution that will be fair to all parties involved without resorting to marginalisation.

Be the first to comment .