Politics

Water Conflicts in The River Nile Basin: The Tragedy of Endowments

This article will try to shed light on the consequences of water conflict in the River Nile basin and the cooperation opportunities among the countries in the region.

Mohammed Alnour* & Marzok Juma**

In 1979, the Egyptian President Anwar Sadat said: “The only matter that could take Egypt to war again is water.” in 1988 then Egyptianpolitician and diplomat Boutros Ghali, who was the sixth Secretary-General of the United Nations from January 1992 to December 1996 predicted that the next war in the Middle East would be fought over the waters of the Nile, not politics.

Water has become a major political issue in the field of international relations, and it is considered as part of the national security for countries and each country tries to secure its water resources by all possible means. The importance of the water resource comes from the fact that it can be the cornerstone towards any developmental projects and a fundamental source of hydroelectric power. The Nile basin countries shared one of the longest river in the world (River Nile) along with other tributaries and lakes. Instead of becoming the basic element for the development in the region, these water resources have become one of the main causes of conflicts and instability in the region. This article will try to shed light on the consequences of water conflict in the River Nile basin and the cooperation opportunities among the countries in the region.

THE NILE RIVER BASIN

Ten countries share the basin of the Nile, and arguably it is considered as the world’s longest river: Burundi, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The basin’s three million square kilometres cover about 10 percent of the African continent.

Nearly, 160 million people depend on the Nile River for their livelihoods, and about 300 million people live within the 10 basin countries. Within the next 25 years, the region’s population is expected to double, adding to the demand for water, which is already exacerbated by the growth of the region’s industries and agriculture.

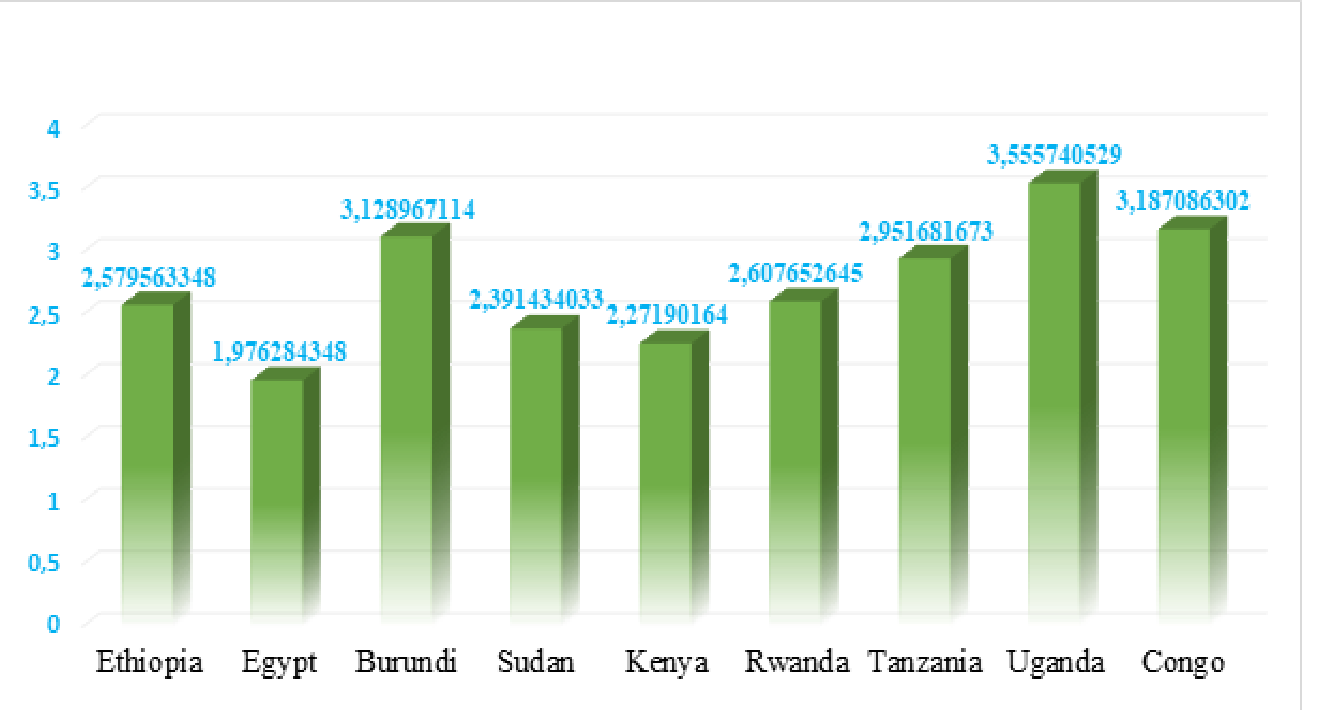

Figure 1 shows the population growth rate in the River Nile basin countries except for Eritrea due to the non-availability of data, it indicates that Uganda and Burundi are the highest countries in terms of population growth; they grow annually by 3.55% and 3.12% respectively. Moreover, Egypt, Kenya and Sudan are among the lowest countries in terms of population growth.

Figure 1. Population growth rate, 2019 (%)

Source: graphed by the authors based on the data obtained from the World Bank (world development indicators)

The constant threat of droughts increases the urgency of the problem, and pollution from land-use activities affects downstream water quality. Except for Kenya, Sudan and Egypt, all of the basin countries are among the world’s 50 poorest nations, making their populations even more vulnerable to famine and disease. Figure 2. indicates that Egypt, Sudan and Kenya are the region’s biggest economic size. Egypt and Sudan are considered as the Nile’s downstream. This further confirms that the Nile upstream are relatively less developed countries.

Egypt holds almost absolute rights to use 100 percent of the river’s water under agreements reached in 1929 between Egypt and Britain (which was then the colonial power in Kenya, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda) and in 1959 between Egypt and Sudan. Since Egypt must consent to other nations’ use of the Nile’s water, most of the other basin countries have not developed projects that use it extensively. Not surprisingly, over the years other basin countries have contested the validity of these treaties and demanded their revocation to make way for a more equitable system of management, Kameri-Mbote, P. (2007).

Several treaties were concluded among the colonial powers, giving priority to the Egyptian demands for the Nile water. However, after the construction of the first Aswan Dam in 1889, Egypt started to fear the probable exploitation of the water resource in the upstream areas.

Under the terms of the 1929 Agreement, Egypt was assigned the right to a minimum of 48 km3 of water per year, while Sudan was assured to receive 4 km3, leaving approximately 32 km3 unallocated. However, this agreement did not include the major upstream water supplier, Ethiopia. The Agreement also noted that the East African countries were not to construct any water development projects in the Equatorial Lakes without consulting Egypt and Sudan. Egypt thus enjoyed the overwhelming rights, as against Sudan, in the utilization of the Nile water.

The period of 1956–1958 witnessed serious disagreement between Sudan and Egypt over sharing of the Nile. Coinciding with the Sudanese objections to the proposed Aswan High Dam, Egypt withdrew from their previous agreement to enable Sudan to build the Roseires Dam on the Blue Nile. The relations deteriorated further when Sudan declared unilaterally its non-adherence to the 1929 Agreement.

Figure2: GDP per capital, 2019 (Constant 2010 US4$)

Source: graphed by the authors based on the data obtained from the World Bank (world development indicators)

In 1957 Ethiopian government submitted a memorandum to both Egypt and Sudan, in which it indicated its natural right to use waters of the River Nile that originating from its lands, and thus its opposition to the signed previous agreements with the colonial authorities, and that it adheres to the principle of exercising sovereignty over the sources of the Blue Nile and Atbara. This rejection of those agreements coincided with announcing the results of a study for the development of Ethiopian agricultural lands which was considered as a response to the High Dam project in Egypt, it was proposed to construct 36 dams and reservoirs that would reduce 5.4 billion cubic meters of the flow of the Blue Nile water.

This inequality in water resources distribution and utilization has resulted in many conflicts, wars and instability in the region of the Nile basin. These consequences have impacted almost all levels of lives especially political practice and governance. In this context, we distinguish between three levels of the state and political instability that prevail in the Nile basin countries:

- Lack of peaceful transfer of power;

The violent change of political leadership in some of the basin countries reflected the seriousness of the process of transferring power and the problem of political succession. Since long ago many of the Nile Basin countries experienced nonpeaceful change and power transfer. There have been many leaders who took power through force and coup in the basin, such as Yoweri Museveni in Uganda, Meles Zenawi in Ethiopia, Omer Al Bashir in Sudan and Assiassi Afewerki in Eritrea. And recently Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi in Egypt.

- Racial and ethnic conflicts;

The countries of the Nile Basin are witnessing racial disparities and a clear ethnic conflict that have been exploited in most cases to achieve particular objectives for the benefit of one ruling group rather than another. Perhaps the Great Lakes region presents a clear model for this type of conflicts, as the ethnic conflict between the "Tutsi" and "Hutu " and their incompatibility with the political borders inherited from the colonial era further caused a political conflict between Rwanda and Burundi, and in some cases, like the Democratic Republic of Congo, and in Ethiopia, the ethnic conflict led to the emergence of the collapsed state pattern appeared in the post the era of colonialism.

- Civil wars and liberalist movements;

Rebel and the operations of armed fighting groups within the borders of many of the Nile basin countries have perpetuated political instability for the existing regimes in these countries. Among the region’s most dangerous wars are the civil war in South Sudan and the Darfur region, and armed conflicts between government forces and opposition groups in Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR COOPERATION IN THE NILE RIVER BASIN

Conflict over the Nile’s waters could fan existing conflicts in the Greater Horn of Africa, making them more complex and harder to address. Tensions in the Greater Horn of Africa are of great concern to the international community, due to its volatility and proximity to the Middle East. Conflicts emerging in the Nile basin might spread political, social, and economic instability into the surrounding areas.

In a river basin, conflict is most likely to emerge when the downstream nation is militarily stronger than upstream nations, and the downstream nation believes its interests in the shared water resource are threatened by the actions of the upstream nations. In the Nile basin, the downstream nation, Egypt, controls the region’s most powerful military, and fears that its upstream neighbours will reduce its water supply by constructing dams without its consent.

By coming together to jointly manage their shared water resources, countries build trust and prevent conflict. In the face of potential conflict and regional instability, the Nile basin countries should continue to seek cooperative solutions and the political will to develop a new legal framework for managing the Nile should continue.

In 1999 the River Nile basin countries have agreed on some level of cooperation when they developed the high-level Nile Basin Initiative (NBI). The NBI has served as a catalyst for cooperation in the search for a new legal framework for the management of the Nile.

However, the Nile Basin Initiative is not enough; civil society must be involved. Since the inhabitants of a river basin play critical roles in the success of any international agreement, interstate negotiations should also include stakeholders and NGOs beyond the national governments.

Moreover, the Nile basin countries should recognize that endowments such as water resources can be a pathway to peace rather than war. Besides, water diplomacy and negotiation can be used to resolve the problems in the Nile basin region.

Developing the capacity of civil society groups to ensure they can meaningfully contribute to basin-wide initiatives. Such capacity building will bridge the endowment gap between civil society and government.

In conclusion, we reaffirm that the only way to tackle the issue of water resources in the River Nile basin is through negotiations and dialogue supported by the political will. And above all, the countries must recognize the rights of each country in its water to meet the needs and to build a sustainable developmental project. Other solution could be very costly and their consequences are unpredictable since in this region there are very high geopolitical discrepancies among the so-called superpowers.

*mohamedmershing88@gmail.com

**marzokjuma571@gmail.com

Abdelazizabdalla000@mail.com

March 08, 2021 Mon 13:58

It's a very nice essay. countries in rever Nile have to wake up for this a weariness before the time lift.